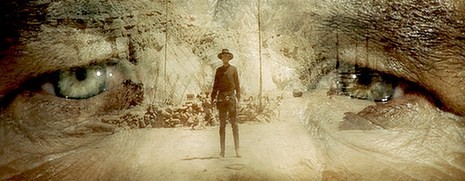

GHOSTS AND AVENGERS, from Shakespeare & Leone, to Eastwood & Garrone

To Alex Cox

Sergio Garrone's spaghetti western Django the Bastard (and few readers won’t be aware of that) is often said to have inspired Clint Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter. True or not, both westerns share a unique story element: the avenger is (or seems to be) a ghost who comes back from the great beyond to set things right here and now. In this essay I’ll discuss the character of the ghost-avenger, both within the context of the western movie and the context of narrative art. I’ll also try to analyze both films, one Italian, the other American, in their own socio-cultural perspective, and show they’re both deeply rooted in their own specific cinematograph tradition, respectively the Hollywood western and the Italian ‘Civil War’ revenge western. Departing from Alex Cox’ notes on the similarities between the Jacobean revenge tragedy and the spaghetti western, I’ll also try to illustrate that both were disguised comments on recent historic development in the countries the films were produced, Italy and the United States. Finally I’ll weigh one against the other within the genre of the gothic western.

# The Bastard and the Drifter

It is only revealed in the final scene of High Plains Drifter that Clint’s drifter is not a normal human being. When the drifter is about to leave the town of Lago, the dwarf he made sheriff and mayor, tells him he still doesn’t know his name. “Oh yes you do”, says the drifter, and the camera turns to the grave of the sheriff who was whipped to death in the town’s main street years before. The most logical conclusion is that the drifter is a reincarnation of the murdered sheriff, so has avenged his own death. While the identity of the drifter is left more than a bit ambiguous throughout the movie , Anthony Steffen’s Django in Sergio Garrone’s Django the bastard is almost immediately exposed as a ghost by his ability to appear in (and disappear from) inaccessible places; he really haunts the movie, sliding in and out of frame, appearing in backgrounds, silhouetted against the sky or outlined in a phosphorescing patch of fog. True, he is wounded by one of the two characters who seem to have some spiritual (and physical?) contact with him, a lunatic, who’s also the younger brother of the film’s main villain. The scene with the lunatic pointing at Django’s blood on his hands and screaming “Look it’s his blood, he’s real”, is genuinely confusing. Is he a real person after all? The final scene of the movie gives us a definite answer: the second person who manages to get in contact with him, Alida, the wife of the (by then dead) lunatic, proposes Django to part with him, so they can live happily ever after. Django rejects her by saying they won’t live forever, and then he’s gone, as if he went up in smoke. The contact was spiritual, won’t ever be physical. He was a ghost after all. Or better: he was a ghost-man, living between the two worlds. Like the drifter he had access, at least temporarily, to the world he came from, to avenge his own death.

# Harmonica and Mortimer

It is generally overlooked that the final scene of Django the Bastard is reminiscent of the end of Once upon a Time in the West, that is the scene with Harmonica rejecting Jill. Several people attending pre-release showings of the movie thought Harmonica was a ghost, and it seems the controversial ‘nursing scene’ with Bronson making a sling for his wounded arm, was shot in order to convince viewers Harmonica was real (1). Some say Leone even considered for a while to treat Harmonica as a ghost, but rejected the idea after ample consideration. Harmonica is no ghost, but he’s so obsessed with his mission that he no longer seems a normal human being (after all, who would reject Claudia Cardinale?): asked for his name, he can only answer with other people’s names, people whose violent deaths he wants to avenge. In his book, Alex Cox draws a parallel between Steffen’s Django and Harmonica, stating that their behaviour on screen is similar (2). Have both Garrone and Eastwood elaborated an idea present in rudimentary form in Leone’s movie? It seems not impossible. It’s dubious whether Eastwood saw Django the Bastard, but we can be sure he did see Once upon a Time in the West. Like Harmonica, the bastard and the drifter seem to live between the worlds, but they come from different sides: Harmonica is so obsessed with death that he no longer behaves like a real person, as if he’s no longer alive, but not yet dead; the bastard and the drifter are still obsessed by what happened during their last moments on earth, there’s still some life in them left, although they are, so to speak, already dead.

Somehow it’s an uncomfortable feeling that dead is the end, that we live only for a short time and are dead for a very, very long time in the immense universe we’re part of (we’re stardust, they say). But it’s probably even more frightening to think that dead is not the end: this notion could imply that we’re still worried in the afterlife about what happened to us while we were still alive, and are not able to do something about it. Watching a character like Harmonica, we have the feeling he has been on the other side, and has noticed that things weren’t okay. He has spoken to the dead, and they have asked him to set a few things right before he joins them in the afterlife for ever. In Greek literature we meet several stories about the living visiting the Underworld, the Greek equivalent of the Afterlife, talking to deceased friends and relatives, learning how they were slaughtered. There’s no indication that Harmonica actually has been in contact with the dead, most probably he simply cannot banish the memory of his viciously murdered brother from his mind. Still the idea of a contact between the living and the dead might have gone through Leone’s head while making the movie. After all the story of Harmonica is a revenge story, which makes it difficult to ignore the most famous revenge story in world literature, Shakespeare’s Hamlet (3). Unlike Harmonica, the Danish prince Hamlet has not witnessed his relative’s death, nor has he paid a visit to the dead in the afterlife: quite on the contrary, a person from the other side, his late father, is visiting him, telling him he was killed by his brother, who subsequently has married Hamlet’s mother.

It should also be noted that even within the context of the spaghetti western, the Harmonica character didn’t fall out of the blue sky. Ever since Colonel Mortimer took the train to Tucumcari in For a Few dollars More, the genre had created avengers obsessed with their cause: the mere presence of objects associated with the cycle of violent death and revenge, is an indication of the fact that these obsessive thoughts were literally taken for a kind of disease. Both Colonel Mortimer and El Indio keep a watch that brings back memories of the violent death of a young girl, Mortimer’s sister, who committed suicide after the bandit El Indio had raped her and killed her lover. El Indio, the rapist and murderer, has become a drug addict haunted by bad memories, but Colonel Mortimer has also become an emotionally crippled man. Once a brave and important man - an officer in the army - he has become a wandering bounty hunter, but in the end, after he and Monco have killed the bandits, he refuses the accept the bounties on their head. This clearly implies that his profession was not part of his identity: he only became a bounty hunter because this profession enabled him to spent years and years on tracking down the murderer of his beloved sister. Once he has killed the man, there’s no need to exercise the profession any longer. His mission is accomplished, his life over: the very idea that kept him alive, was the prospect of killing the man who ruined his life, who had, so to speak, killed him, years before he would actually die.

In a conversation with Chris Frayling, Leone emphasized that he chose Lee van Cleef for the part because of his appearance, he wanted to have him at all costs, “because when I think of the character, I picture him” ; when he first saw Van Cleef, he reminded him of “a grizzled old eagle”; he said to his production manager to sign Van Cleef on the spot, without even talking to him, because he was afraid a conversation would influence his decision to give him the Colonel Mortimer part (4). Leone could identify the ideal actor for a part in one single glimpse. That was part of his brilliance. What he must have sensed and felt when he first saw Van Cleef for the first time, was that no other actor in screen history had ever looked more like a scarecrow, a grim reaper. Or, for that matter, like a man who was still living, but already dead.

# Proust and Freud

The associative style, with objects launching memories and taking people back to an emotionally charged past, used by Leone in both For a Few Dollars More and Once upon a Time in the West, is associated above all with Marcel Proust’s immense novel A la Recherche du Temps Perdu (1909 – 1922). In the most famous scene of the novel, long forgotten memories from the past start welling up when the narrator dips a madeleine cookie into his cup of tea. He used to do this as a child, and it’s the taste and smell of the wet cookie that leads him back to his childhood days. In Leone’s movies the madeleine cookies have been replaced by objects like a musical watch and a harmonica. Leone was fascinated by Proust (Once upon a Time in America would be his most Proustian film), but like most artists of his generation he was also fascinated by Freud and psycho-analysis. The associative memory as described by Proust, is called the involuntary memory (recollections are evoked without a conscious effort, by an object, taste or smell) as opposed to the voluntary memory (resulting from a conscious effort to recollect the past). The remarkable aspect of Leone’s movies, is that a involuntary memory is made voluntary, by deliberately provoking it by means of an object. In other words: the object has become a sort of Freudian fetish, only this time its function is not to provoke any sexual arousal, but to remind the user of the very moment that has become his raison d’être. The Slovanian philosopher and psycho-analist Slavoj Zizek has related the Harmonica character to Lacan's conception of 'subjective destitution': Harmonica can only preserve a minimum of coherence in the face of a childhood trauma through a form of personal madness, which translates in an identification with the harmonica: he plays when he's supposed to talk, and talks when he's supposed to play (5).

The Proustian/Freudian narrative, introduced by Leone, would turn out to be very fruitful within the spaghetti western genre. In Death rides a Horse the avenger has witnessed the massacre of his family as a kid; as an adult he recognizes the murderers by a special sign (a scar, a tattoo, a necklace etc.) he spotted on that fatal night, and put away in his sub-consciousness. In Cowards don’t Pray the avenger has a spasm of grief and anger every time he notices a shiny objects that reminds him of the distinctive badges the murderers of his fiancée were wearing; due to memory loss, he cannot link the right persons to these ‘signs’, which will eventually drive him insane and turn him into a maniacal killer. In Arizona Colt the identification of the character with his fetish, a watch, has brought him so far that he has named himself after it: Gordo Watch. No wonder: in order to get hold of it, he has committed the most Freudian crime of them all: he has killed his own father.

Notes:

- 1. Trevor Willsmer – Once upon there was the West … - Booklet added to the Paramount Special Collector’s Edition

- 2. Alex Cox: 10,000 Ways to Die, A director’s take on the spaghetti western, p. 253-257

- 3. Christopher Frayling: Sergio Leone, Once upon a Time in Italy, p. 75-76; In an interview, Leone told Chris Frayling he often felt (while making a film) like the Bard, because he had realized that Shakespeare could have (and would have) written great westerns; he also mentioned Homer as a source of inspiration.

- 4. Christopher Frayling: Sergio Leone, Once upon a Time in Italy, p. 85

- 5. Zlavoj Zizek: The Undergrowth of Enjoyment, p. 33

Films treated or referred to in this section:

- Django the Bastard (Django il Bastardo - 1969, Sergio Garrone)

- High Plains Drifter (1973, Clint Eastwood)

- Once upon a Time in the West (C'era una volta il West - 1968, Sergio Leone)

- For a Few Dollars more (Per qualche dollaro in più - 1965, Sergio Leone)

- Death rides a Horse (Da uomo a uomo - 1967, Giulio Petroni)

- Cowards don't pray (I Vigliacchi non pregano - 1967, Mario Siciliano)

- Arizona Colt (1966, Michele Lupo)

--By: Scherpschutter