An Essay on the Politics of the Spaghetti Westerns of Sergio Leone

The Spaghetti Western genre was a fiercely political brand of filmmaking. It took the American archetypes of the genre and reversed them completely, a subversion rejecting what had gone before and the traditions with them. The very idea in the tumultuous sixties of turning one of the most identifiably American genres (and all the connotations such an idea provokes) was inherently political. The Spaghetti Western often criticised America and its foreign policy using that very country's own iconography, turning the United State's own highly cherished symbolism against itself.

The Zapata Westerns are of course the most identifiably political of the Spaghetti Westerns: films like A Bullet for the General (1966), The Mercenary (1968) and Tepepa (1968) are revolutionary parables, using the Mexican Civil War at the turn of the century as a vehicle for the directors' left wing revolutionary politics, using them to make sharp points about the Italy they lived in during the declining years of the 1960s. There was a genuine feeling of socialist change was about to happen in Europe and directors like Damiano Damiani and scriptwriters such as Franco Solinas saw these films as an attempt to politicise the working man, a trigger if you will for the coming revolution.

However, it wasn't merely these Zapata films that were stridently political; so were the "normal" Spaghetti Westerns. Often, the villains would be powerful, evil capitalists grinding down poor workers with hired mercenaries and bandits. The heroes (if such a thing truly exists in a Spaghetti Western) were frequently solely motivated by greed and they were punished for it. Characters like Django and Johnny Yuma would undergo mutilation for their attempts to acquire wealth and riches and might even die.

Yet how does the founder of the genre, Sergio Leone, fit in to this maelstrom of strident, revolutionary politics? His films are often regarded as apolitical, concerned more with making supremely enjoyable action adventures and then later “art films” than politics per se. However upon closer viewing, it can be seen that he did indeed politicise his films. It wasn’t always as brazenly political as some of this contemporaries like Sergio Corbucci or Sergio Sollima, but the politics was there.

A Fistful of Dollars

|

In 1964, the Western was dead and ripe for reinvention. In Hollywood they had become the preserve of television with series such as Wagon Train and Wanted: Dead or Alive. A young director called Sergio Leone, like all film lovers, a fan of the Western, wanted to make one, a film he could call his Western. It would change cinema.

The script for A Fistful of Dollars seems to have had numerous hands involved along with Leone, mainly Duccio Tessari (director of the later “Ringo” films), Fernando Di Leo (whose Italian crime films from the seventies are a high watermark of the genre) and Tonino Valerii, another prominent future Spaghetti Western director and associate of Leone. Cox (1) reports that the original screenplay ran an eye-watering 358 pages, a length that would run around six hours on the screen. This mammoth span is misleading: it suggests that they were working on a visionary, original script that was bursting with ideas. The truth is a lot simpler.

Sergio Leone had seen Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo, made in 1961 but not released in Italy until 1963, and loved it. He loved it so much that A Fistful… is in fact a remake of Kurosawa’s samurai film transposed to the West (this was not the first nor would it be the last time for Kurosawa’s films). Due to this, the film is probably the most politics-free film Leone made, but despite this, a key change was made to Yojimbo’s story: here, instead of two feuding Japanese gangs, we have Mexican verse gringo outlaws. In one crucial detail, Leone makes it more than just rivalry between the gangs; the hatred stems from racism too. This racial element was to become incredibly influential to the genre and many, many subsequent Spaghetti Westerns would copy this set-up.

Why did Leone do this? Anyone who even only casually followed the current events in the United States at the time would have been aware of the Civil Rights movement and black power. It’s one of the few major changes made and gives the film a different perspective. It is also interesting to note how Mexicans were treated with in Spaghetti Westerns: most are casually stereotypical portraits, but it should be said that rarely are they shown to be completely evil like their American capitalist counterparts. Mexican bandits might do bad things, but all they really want is women and drink. The films might stop short of sympathy, but it’s not hard to imagine the left wing intellectuals making Spaghetti Westerns as not empathetic towards these common men making a living in a world of corruption and racism.

A Fistful of Dollars was a huge world wide success at both home and abroad. Unsurprisingly, a follow-up was demanded from the producers and what was made resulted in the archetypical Spaghetti Western.

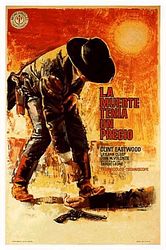

For a Few Dollars More

|

This 1965 film is about a bounty hunter, Manco (Clint Eastwood). Only in the post-credits caption, these hunters are called something rather different:

Death, sometimes, has its price.

This is why the Bounty Killers appeared.They are Bounty Killers, not Bounty Hunters. Leone is making an important distinction here; this is no sport, it’s not even law enforcement. It is killing people for money. It is small wonder then that Colonel Douglas Mortimer (Lee Van Cleef), seeking revenge on El Indio (Gian Maria Volonte), is the noblest character in the film. He is the only person that isn’t motivated by greed, an all consuming lust for money. Leone’s world had little room for gallantry and “the code of the West”. Hollywood and John Wayne was a long way away.

The villain of the film, El Indio, is shown smoking dope frequently throughout the movie. In Spaghetti Westerns, anyone who uses drugs is normally beyond bad: they’re cruel, evil and sadistic, capable of horrendous acts of brutality. Here, El Indio has a baby murdered. In a time when drug use was becoming more and more mainstream and popular with young people around the world, it’s intriguing to see that these left wing filmmakers were always against recreational drug use. Sergio Corbucci, a director more stridently open about his politics in his Spaghetti Westerns than Leone, said in an interview with a French magazine (2):

It isn’t that much of a surprise that their stance on drugs is so fierce; Spaghetti Westerns main target audiences in Italy (although their huge success crossed every strata of society) were working class people who, irrespective of any left wing leanings they might have, would of course have disliked the younger generation who they would have seen as wasting their lives away on drugs. The working class was a position in society all good revolutionary socialists like Damiana and Solinas identified themselves with and their outlook on drugs would have been much the same.

The Good, the Bad and the Ugly

|

An epic in the fullest sense of the word, this Spaghetti Western from 1966 is a complex tale of double and triple cross between the ironically named trio of “the Good” (Blondie – Eastwood), “the Bad” (Angel Eyes/Sentenza – Van Cleef) and “the Ugly” (Tuco – Eli Wallach). It is one of the key films on the American Civil War (1861 – 1865), a conflict that along with the Crimean War (1853 – 1856) ushered in the modern age of war with its use of new industrial technologies and weapons. Sergio Leone’s anti-war view, shared by many of his contemporaries, manifests itself multiple times throughout the film.

The first time the Civil War really makes any sort of impact on out selfish “heroes” is when Blondie and Tuco have just left Tuco’s brother’s monastery. Driving alone in a horse and carriage, disguised as Confederate soldiers, they see a regiment of soldiers coming towards them. The pair start shouting “long live the South!” sentiments hoping to fool the troops and be allowed past. Unfortunately for them, these are Unionists, their uniforms coated in a thick layer of dust, making their blue uniforms grey. Blondie and Tuco are captured, bewildered at this turn of fate.

Leone is making an important point here of the inter-changeability between the two sides in the conflict. To him, there is no difference between them. He makes it again during the battle scene where the Confederate and Unionist forces are separated by a bridge. There is no disparity in tactics here or weaponry and the fresh faced young soldiers are charging to their death all look the same.

In the Unionist prison camp that Tuco and Blondie are taken to where Sentenza has insinuated himself as a Sergeant, beatings are handed out callously and executions are regular. However, unexpectedly, the Union officers are treated with sympathy. The Commandant of the prison camp (Antonio Molino Rojo) is furious at Sentenza’s cruelty, but he is laid low by gangrene and helpless. Sentenza deals with him with an amused contempt. The other officer, Captain Clinton (Aldo Guiffre) charged with sending his men to their short, bloody deaths in a bid to capture the bridge, is shown as a man resorting to drink to bare his terrible burden. This show of pity towards the two officers and military men in general is in stark contrast to other directors of Spaghetti Westerns of the time where anyone in a uniform is a devious murderer.

Even Blondie and Tuco are sobered by the sight of carnage at the river; Blondie even says the clichéd line of “Never seen so many men wasted so badly”. Later, he shows some kindness to a dying soldier by giving him a smoke and some drink in exchange for the character’s now iconic poncho.

Religion is treated piously in the film, with Tuco’s brother Father Pablo (Luigi Pistilli) perhaps the only character in the film shown to have any honour (something of a scarcity in the genre; many priests are shown to be racist hypocrites often sided with a villainous capitalist). There are a number of reasons Leone didn’t share the same visceral aversion to the clergy Corbucci did. Cox argues that because his movies were being funded by a Hollywood studio by this point, Leone had to go along with traditional sentimentally about the Catholic Church. However, I believe there is a less cynical reason. Italy was and still remains a devoutly Catholic country; the working class might be deeply suspicious of organised religion and its connections with power and the Cosa Nostra, but they are still Christian and the lower echelons of the Church would be afforded respect. Leone wasn’t as radical politically as other directors of the era, Spaghetti Western or otherwise, and slipping into secure, long held notions about religion would have been easy for Leone, especially as he was at the same time trying to create his largest and grandest Western yet.

There are many, almost throwaway, shots of the destruction of war. Towns that our trio pass through are often devastated, with retreating armies shooting deserters who have just dug their own graves or prisoners shackled to the fronts of trains. War is hell, the film says, so what difference does it make, during all this madness, whether some are killed by a bullet from one of the treasure hunter’s gun or from a Unionist or Confederate rifle?

Once Upon a Time in the West

|

Bernardo Bertolucci co-wrote the screenplay for "Once Upon a Time…" along with Dario Argento and Leone. Later an intensely provocative filmmaker, he made not just The Conformist (1970), a film examining fascism in Italy in the 1930s, but Last Tango in Paris (1972) as well. He was and still remains a different kind of Italian director to Leone. Instead of cutting his teeth on cheap exploitation films, his first film The Grim Reaper (1962) already showed his interest in politics and justice. So a Spaghetti Western is outside of what Bertolucci normally did at first glance.

Superficially, the film is Leone’s (successful) attempt to make a “super-western”. Not only a compendium of allusions to great American Westerns, but a film that marks the end of the West, both in actuality and in cinema. Sergio Leone had a cast of legends to sketch out his drama: Henry Fonda, Charles Bronson, Claudia Cardinale, Jason Robards; actors he’d pursued in the past (he had sent the script for A Fistful…' to Fonda) but now, thanks to his reputation as not only one of the world’s foremost directors, but also one of the most bankable, they came to make in the words of film critic Peter Watts: “Leone’s timeless monument to the death of the West” (3).

Where is Bertolucci in all this, or Leone’s politics from his past three Spaghetti Westerns? The film is suspicious of “civilisation”, the boom towns that spring up around the ever moving railway and the killers that come with it. Frank (Henry Fonda) is a rapist, a child-murderer in the pay of the railroad magnet Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti); yet even he acknowledges before the final climactic showdown with Harmonica (Charles Bronson), that he is no businessman. Is Leone saying that people can’t change, can’t alter their intrinsic self? Cheyenne (Jason Robards) doesn’t even try to change. He is a bandit, a vestige of the old days, looking on as his world transforms unrecognisably. Harmonica is a cipher, a man so eaten up by revenge that once is quest ends; there is nothing left for him. His world is gone, his raison d'être is dead. Where can he go, but back into the shifting sands?

Only Jill McBain (Claudia Cardinale), the whore from the big city, is a survivor and she lives on through everything the Wild West can throw at her, the last gasp of wilderness; its last vindictive hurrah. Civilisation wins and those that can change are the only real victors. Jill is the only area in the film where there is optimism; only she can bend with the dry, dusty wind of time, of history, of progress. It’s “Sweetwater” in the desert: hope.

As befits one of the most sophisticated and complex films ever made, Leone is too intelligent to think in black and white terms of “good” and “evil”. Frank commits crimes beyond any moral boundaries, yet in acknowledging that he is “a man” like Harmonica, he achieves nobility in death. Likewise, Morton, initially seen as the very epitome of the wicked capitalist, is in fact perhaps the most vulnerable of all the characters. Stricken by tuberculosis, restricted to his private carriage, moving using its grippable gantry, driven on to see his railroad to reach the Pacific, his actions are committed ultimately not out of cold, clinical businessman decision-making, but from passion, emotion, obsession, so very like Harmonica. He too is connected to the West, therefore it follows he must die too. The railroad though, is immortal, it lives on, and like a Pandora’s Box it can never be stopped.

Leone was going beyond the classical socialist reading of malicious capitalism; in humanising Morton he was showing in stark contrast to political, left wing didacticism how such literal ideologies don’t reflect the real world. Spaghetti Westerns as a whole do not and never purported to be physically realistic depictions of the West. They were more than that; they were emotionally accurate. The films were Stendhal’s “mirror of life”: a mirror shows the world, but not completely, for after all, a mirror’s reflection is not quite right, it is not entirely precise; there are concerns greater for an artist than realism in the search for full emotional truth.

Sergio Leone’s ambitions in this film went far further than the Marxist informed Corbucci or Sollima ever attempted; his film went beyond mere genre, beyond politics. It became art. Few filmmakers who aspire to make a movie than could be described as art succeed; the very fact that they are self-consciously aware of what they’re trying to create limits them. Leone, unsurprisingly, does the impossible and accomplishes it with style (the Spaghetti Western way).

Refusing to use political shorthand to describe Morton and the other characters (how easily Cheyenne in other’s hands could have become a simplistic personification of the West!), uses the more universal method of symbolism. Morton uses technology to remain mobile with his own personal train; literally it is progress that allows him to move forward. Change alters everything; the whole movie is about the characters response to it.

The only state of repose known to humans that doesn’t alter is death so it is entirely appropriate that death is intimately linked to everything in the film; it is a “dance of death”, the chill hand touching everyone in the film. Of the five major characters in the film, only Jill and Harmonica live to see the setting Sun; yet they too have been affected. Jill’s husband and step-children are dead and it is hard to believe there is anything left alive inside of Harmonica.

To go beyond politics, to transcend genre and commercialism, to leave your compatriots so very far behind, to go where no one had gone before, is a heady thing to do for an artist. Once there, it takes only but a short while to come back to the very real concerns of the Italian state of mind in the late sixties and early seventies. He would deal with this in his final Spaghetti Western, his first and only Zapata Western, his most overtly political film, the much misunderstood Duck, You Sucker!.

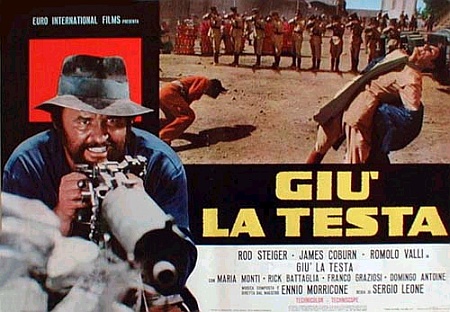

Duck, You Sucker!

|

The young hotshot American director Peter Bogdanovich, who had just made the yet to be released The Last Picture Show (1971) was originally hired to make this 1971 film. Sergio Leone only intended to produce after co-writing the screenplay with Sergio Donati and Luciano Vincenzoni; however the two directors did not get on, both having varying ideas on the best approach. Bogdanovich soon left the project due to their clash of personalities. Sam Peckinpah was then discussed, but finally Leone’s former second-unit director Giancarlo Santi was brought on board. He shot for a few days until the stars, James Coburn and Rod Steiger revolted, saying they had signed on to make a picture with Leone. The Master relented, perhaps even wanting this outcome with the stars swelling his ego by demanding him and him alone to direct.

The film then had a very troubled genesis and the script reflects this. It has a mix of style and tones and Leone maybe wasn’t interested enough to marshal them; after all, what he really wanted to do was make his gangster picture, a film that would eventually become Once Upon a Time in America (1984).

Yet in many ways the film is one of Leone’s most important movies, one of his most personal, more so than the so-called “Dollars Trilogy”. It directly addresses political issues that Leone was concerned with and the final product looks at the Mexican Revolution from a markedly different angle to other movies.

The major mistake a viewer could make while watching the film is to assume, because of its topic and the way it had been dealt with before in Tortilla Westerns like Sergio Corbucci’s Vamos a matar, compañeros (1970), the film is meant to be a straightforward allegory on politics of the early seventies with it advocating a left wing revolution. In fact the movie deals with the Italian trauma of the Second World War and Benito Mussolini’s dictatorship of the country.

In 1943, after the Allied invasion of Italy, the country changed sides from the Axis powers led by Nazi Germany and joined the U.S. and Commonwealth forces. However, Mussolini retreated, taking his government to the north of the country, to Salò, where he established a puppet state, in reality controlled by Germany. This meant that a once united country became divided; both sides were forced to regard each other as traitors and fellow countrymen fired upon each other in anger.

Subsequently, post-1945, Salò became a byword in Italy for Fascist debauchery, exemplifying the worst excesses of Mussolini’s dictatorship. Leone himself said that the Mexican Revolution here was only a symbol. The Mexican Army in Duck… is a stand in for Fascist military, the mass executions in the abandoned sugar mill in the film recalling similar World War II atrocities and the scene where Juan Miranda (Steiger) finds his family and comrades-in-arms massacred in a cave seems to deliberately evoke images of murdered partisans from the Second World War. A lost scene that survives only in stills of Dr. Villega (Romolo Valli) being interrogated by Colonel Günther Reza (Antoine Saint-John) seems to have been shot to make the toturers look like Gestapo, the German secret police.

This identification not with the popular intellectual left wing position of the day but the national psychological scars of Italy still suffered from the war is crucial in seeing that not only was Leone a different kind of director to other Spaghetti Western filmmakers, but in showing his anxieties and preoccupations as an artist.

Still, although working in the main as an allegory for Italy in World War Two, Leone also tackles the revolutionary politics much in fashion. The quote at the start of the film from Mao Tse Tung is almost like a warning to those arm-chair philosophers who would take up arms; there is no glamour here. As Kurosawa’s master-less samurai in Yojimbo said, “It’ll hurt”.

The seventies weren’t the sixties; it was post Manson, post Altamont, post Paris 1968. There is a new found pessimism at play here. Sean Mallory (Coburn) is shown not to truly understand what a revolution means, its effects on the poor peons it’s supposed to help. Then again, Juan is fairly amoral, loyal only to his family and after their deaths, to Sean. Juan at first isn’t a pleasant character and the rapine of a captured woman who had been travelling with well-endowed passengers on a stagecoach verges on tasteless. Leone only has one strong woman in his entire oeuvre, Jill, and here there is no attempt to recreate her.

Sean is perhaps an even trickier character to deal with: he is a member of the Irish Republican Army in 1913 despite the fact in the real world they weren’t formed in 1919 and is depicted killing two British soldiers in Ireland in flashback. Leone obviously had no grasp or interest in Irish history or politics and his choice to have Sean as part of the IRA is an uncharacteristic miss-step. For Leone, Sean was meant to embody the disillusioned revolutionary, complete with slow-motion flashbacks to an impossibly rose-tinted Ireland. However, his choice of the Irish conflict, especially in the 1970s, is evidence that Leone had little understanding of politics outside of Italy and America and a wider European context.

Another aspect of Sean is that, when surrounded by his enemies, he will threaten to blow up himself and all those in the immediate vicinity with his multiple sticks of dynamite strapped to him. Is this Leone’s vision of the ultimate radical, a man who is willing to take out as many of the adversaries as possible, forsaking one’s own life? Or is it a reference to Gianfranco Parolini’s Sabata (1969), where a comparable scene happens? It is hard to tell; the script alternates scenes of graphic violence with a disorientating light-hearted, almost tongue in the cheek approach.

Finally, Duck… operates on two levels: primarily as Leone’s attempt to exorcise the demons of wartime Italy and to a certain extent as a riposte to those who advocated a Communist revolution, claiming that they did not fully understand the implications of what would really happen and the effect it would have on the workers they were supposed to be helping.

Conclusion

Sergio Leone was among the finest directors of his generation. He made some of the most influential films of the era and his legacy to filmmaking lives on and will continue to do so. His brand of cinema was never as political as others from the same decades, but, as no man is an island, no artist works independently from the world they live in. Leone was a product of his times and the politics his films exhibits, particularly from The Good, the Bad and the Ugly onwards, show how he responded to the Marxist intelligentsia, slyly undercutting the doctrines and seeing with clarity the truly important facets of the human condition.

- (1) Cox, Alex; page 33, 10,000 Ways to Die: A Director's Take on the Spaghetti Western, Kamera Books, 2009.

- (2) Cox, Alex; page 269, 10,000 Ways to Die: A Director's Take on the Spaghetti Western, Kamera Books, 2009.

- (3) Watts, Peter; page 780, Time Out Film Guide 2009, Time Out Guides Limited, 2008.

Lobby Cards and Posters

By John Welles 12:13, 23 January 2013 (CST)